Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, 57-58 (2010 (pub. 2012)), 25 paragraphs.

Tom Mole is Reader in English Literature and Director of the Centre for the History of the Book at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. His research interests include: book history and print culture; literature of the Romantic period in Britain, especially Lord Byron; Romantic periodicals and reviews; the cultural history of celebrity; and the theory and practice of interdisciplinarity. Contact him at tom.mole@ed.ac.uk.

Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net, 57-58 (2010 (pub. 2012)), 25 paragraphs.

Byron’s Romantic Celebrity: Industrial Culture and the Hermeneutic of Intimacy

Byron’s Romantic Celebrity: Industrial Culture and the Hermeneutic of Intimacy

Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007

Read more on the publisher’s website

Purchase from Amazon.com

Winner of the Elma Dangerfield Prize, 2009

![]()

“One of the most stimulating books written on Romantic poetry this year”

“This superb book provides an adroit analysis of the ways that a specifically Romantic celebrity culture informs Byron’s oeuvre – from the ‘Frame Bill’ ode to Don Juan. Yet it does much more than that. In fact, Mole manages to recontextualize the entire concept of Romantic fame as a complex interplay between industrial print culture, historical individuals, and the readerly paradigms of the era. It is this broader lens that enables the book to shine new light on such issues as Romantic subjectivity, authorship, visual iconography, and the nineteenth-century dialectic between public and private.”

“At last Tom Mole offers a study of Byron’s celebrity that focuses on his diverse and at times groundbreaking body of work rather than his sensational biography. Each chapter examines not only a certain aspect of Byron’s fame but also one of his poems. Most of Byron’s major works, as well as some less expected poems, are treated to Mole’s combination of cultural-material analysis and illuminating close reading. […] Mole’s book makes a significant contribution not only to Byron scholarship, but to the study of celebrity culture more generally. […] Mole writes with an effortless blend of accessibility and intellectual gravitas.”

“Anchored by a scrupulous attention to the historical and bibliographical contexts of Byron’s poetry, the book offers […] new ways of thinking about why Byron captured public attention so intensely. […] Mole’s study has its deepest roots in the archive of Regency print culture: each chapter is informed by meticulous bibliographical research, and often by genuine scholarly discovery. […] The wonderful depth and tenacity of Mole’s investigations […] [is] palpable in the many fine readings and scholarly contributions in evidence throughout. […] [A]s a multi-faceted demonstration of Byron’s Romantic celebrity, it is indeed an extraordinarily valuable contribution.”

“Byron’s fame never ceases to fascinate. […] Of all the books […] most worth reading with regard to the idea of celebrity are Tom Mole’s Byron’s Romantic Celebrity: Industrial Culture and the Hermeneutic of Intimacy and Claire Brock’s The Feminization of Fame.”

“This monograph succeeds admirably in combining sensitive textual analysis, careful bibliographical research and awareness of the broader material aspects of the history of print culture.”

“Tom Mole’s study of Byron’s celebrity has found a genuinely new way of approaching the poet and his work”.

“The book begins with a beautifully articulated discussion fo the etymology of ‘celebrity’ […] Chapter 7, on Childe Harold III, illustrates all the strengths of the book in provocative contextual relocation, sharp attention to the material history of the poems and perceptive close reading. […] This is a brilliant and compelling section. […] This is a stringent and searching book and timely one, too[.]”

“In a superb closing chapter, Mole shows how Don Juan adopts an anachronistic conception of subjectivity as a direct critique of the celebrity culture that Byron had helped instigate. Romantic celebrity, for Mole, helped in the development of modern ideas of selfhood as deep and developmental. The genius of Don Juan is that it undermines these assumptions from the inside. It is a fitting conclusion to an excellent book.”

“Tom Mole’s Byron’s Romantic Celebrity: Industrial Culture and the Hermeneutic of Intimacy, despite its mouthful of a subtitle, is nonetheless a riveting study of its subject. […] Mole’s study is concise, often groundbreaking. […] The final chapter, ‘Don Juan: Celebrity and the Subject of Modernity,’ offers penetrating analyses of several key passages in the poem. Mole is particularly good in discussing Byron’s dislike of ‘cant’ […] On the basis of this chapter, one might wish from Mole a full-length study of Byron’s greatest poem. The chapter includes superb discussion of Montaigne’s influence on Byron. […] [T]he book on the whole lives up to its author’s billing. It does advance our knowledge of Byron’s achievement considerably.”

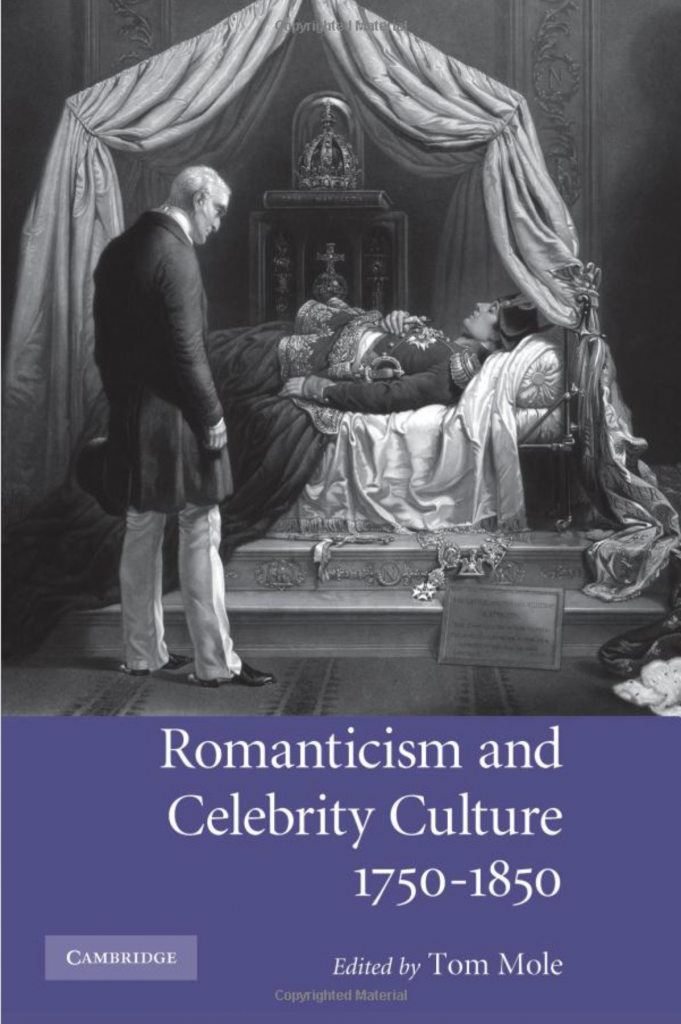

In Romanticism and Celebrity Culture, 1750-1850, Ed. by Tom Mole, 2009

by Ghislaine McDayter

The Byron Journal, 37.2 (2009), 171-73.

“The essays in this book make a convincing case for the sorrows of celebrity, as well as its alleged charms, in the pre-photographic, pre-cinematic age.” TLS

International Journal of Cultural Studies, 11 (2008), 343-361

McGill Reporter – 7 February 2008 – View as HTML

Britney Spears has been admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Posh Spice has a new tattoo. Paris Hilton has been photographed wearing five different outfits in one day. And Amy Winehouse has gone to rehab after all.

These are just a few of the stories that have emerged from the seemingly unstoppable industry of celebrity gossip in the last week. While Britney and Amy are obviously in crisis, it’s business as usual for Paris and Posh. Yet these stories are reported next to each other as though of equal importance. They also appear alongside coverage of more newsworthy events, such as the battles for U.S. presidential nominations. But even that sometimes seems more about celebrity gossip than substantive policy. With Oprah stumping for Obama, Arnold Schwarzenegger supporting John McCain and Chuck Norris (who?) endorsing Mike Huckabee (who?), action heroes and daytime divas have generated almost as many column inches as some of the candidates.

We live in a culture saturated in celebrity, where the logic of celebrity seems to be rapidly colonizing all areas of public life. New starlets appear (Hello, Paris), old stars fade away (So long, Chuck), and images are reinvented (Welcome back, Arnie). How should we understand this situation, and where did it come from?

Although, as a culture, we are obsessed by celebrities, very few of us have given much thought to the history of celebrity culture. Most of us assume that we’ve always had celebrities, or that our fascination with celebrities is unprecedented in its intensity. But neither of these assumptions is true.

Celebrity culture began at an identifiable point in the past and we can track its historical shifts with some precision. Some have suggested celebrity emerged with the development of film at the end of the 19th century. I suggest that they’re right to link celebrity with a new technology, but they’ve got the wrong one. The crucial technology was a better printing press, and the innovations leading to it occurred some 100 years earlier.

Industrial printing, rising literacy rates and improved distribution infrastructure created a sense of “information overload” never before experienced. These conditions also left readers and writers feeling alienated from each other. Unlike earlier ages when manuscript circulation or subscription publication was the norm, there was no longer any prior connection between them. Celebrity culture originally emerged to solve these problems. Authors, publishers, artists, engravers and journalists worked together to brand an individual’s identity so he or she would stand out from the crowd. As a result, actors such as David Garrick, sportsmen such as the boxer Daniel Mendoza and authors such as Lord Byron became the first modern celebrities.

A new vocabulary was required to refer to these new figures on the public stage. In 1751, Samuel Johnson recalled a time when he “did not find [him]self yet enriched in proportion to [his] celebrity.” He used the word to name a desirable personal attribute for the professional man of letters. A century later, in 1849, a character in one of Dinah Mulock Craik’s novels asked, “Did you see any of those ‘celebrities,’ as you call them?” Using a form of the word that was evidently still unfamiliar, Craik employed it as a concrete noun. Something important about the nature of fame had changed in the century that separated Johnson from Craik. Celebrity was no longer something you had, but something you were.

Celebrity culture helped people to feel less detached from their idols by giving the impression that to read a poem by Byron or to look at a picture of Garrick was to experience a kind of relationship with them. In my book on Byron, I call this “the hermeneutic of intimacy,” because it’s a way of reading that constructs a powerful emotional connection between the celebrity and the consumer.

In the age of 24-hour gossip, you can get more updates about Britney or Amy than you get about the lives of your own family. Some devoted fans feel emotionally closer to their idols than to almost anyone they’ve met in the flesh.

So next time you open a magazine to check out the latest long-lens pictures of Britney’s public meltdown, take a moment to zoom out and remember that you’re taking part in a cultural phenomenon whose history stretches back farther than you might think.

Tom Mole is an assistant professor in the Department of English and the author of Byron’s Romantic Celebrity (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007). He is currently editing a collection of essays called Romanticism and Celebrity Culture 1750-1850, to be published by Cambridge University Press.

In Byron: The Image of the Poet, Ed. by Christine Kenyon Jones, 2008

In Byron: Heritage and Legacy, Ed. by Cheryl A. Wilson, 2008

In Liberty and Poetic Licence: New Essays on Byron, Ed. by Bernard Beatty, Tony Howe and Charles E. Robinson, 2008